Tutorial for cli2: Dynamic CLI for Python 3¶

Architecture¶

Overview¶

cli2 is built on 3 moving parts which you can swap with your own or inherit from with ease:

Command: Represents a target callback, in charge of CLI args parsing and execution, can serve as entry point.Group: Same as above, except that it routes multiple Commands, can serve as entry point as well.Argument: Represents a target callback argument, in charge of deciding if it wants to take an argument as well as casting it into a Python value.

You probably won’t care about the latter even for custom use cases.

Command¶

Create a command from any callable:

import cli2

def yourcmd(somearg: str):

"""

Your own command.

:param somearg: It's some string argument that this function will return

"""

return somearg

# this if is not necessary, but prevents CLI execution when the module is

# only imported

if __name__ == '__main__':

cli2.Command(yourcmd).entry_point()

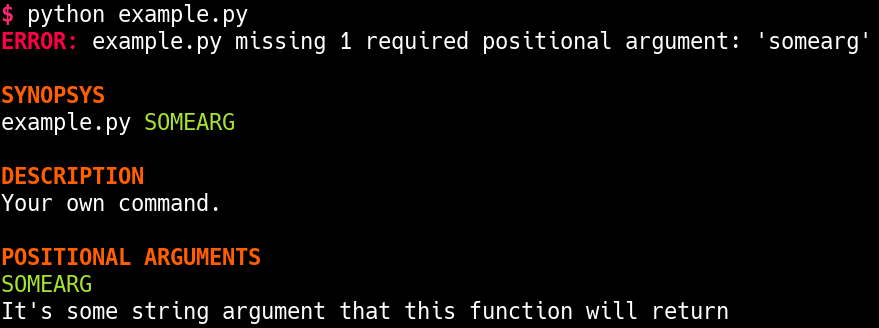

Running the script without argument will show the generated help:

Complex signature¶

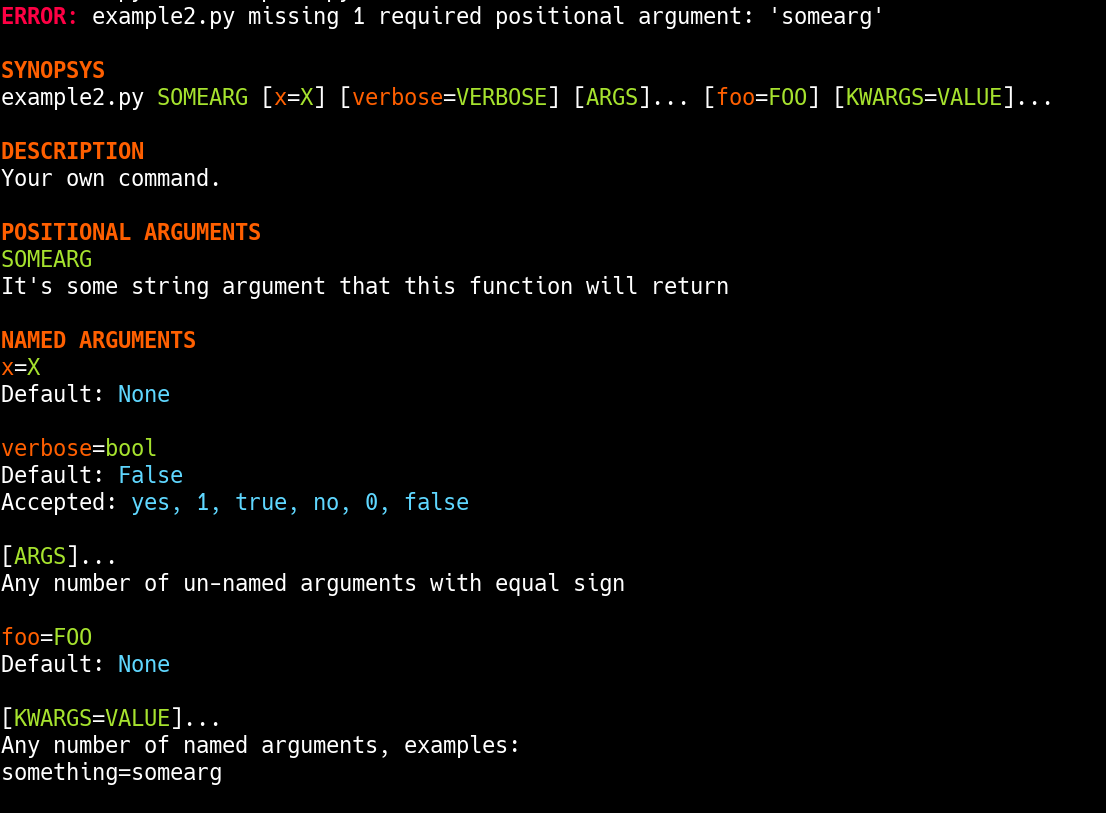

The same function with a rich signature like this:

def yourcmd(somearg, x=None, verbose : bool = False, *args, foo=None, **kwargs):

Will display help as such:

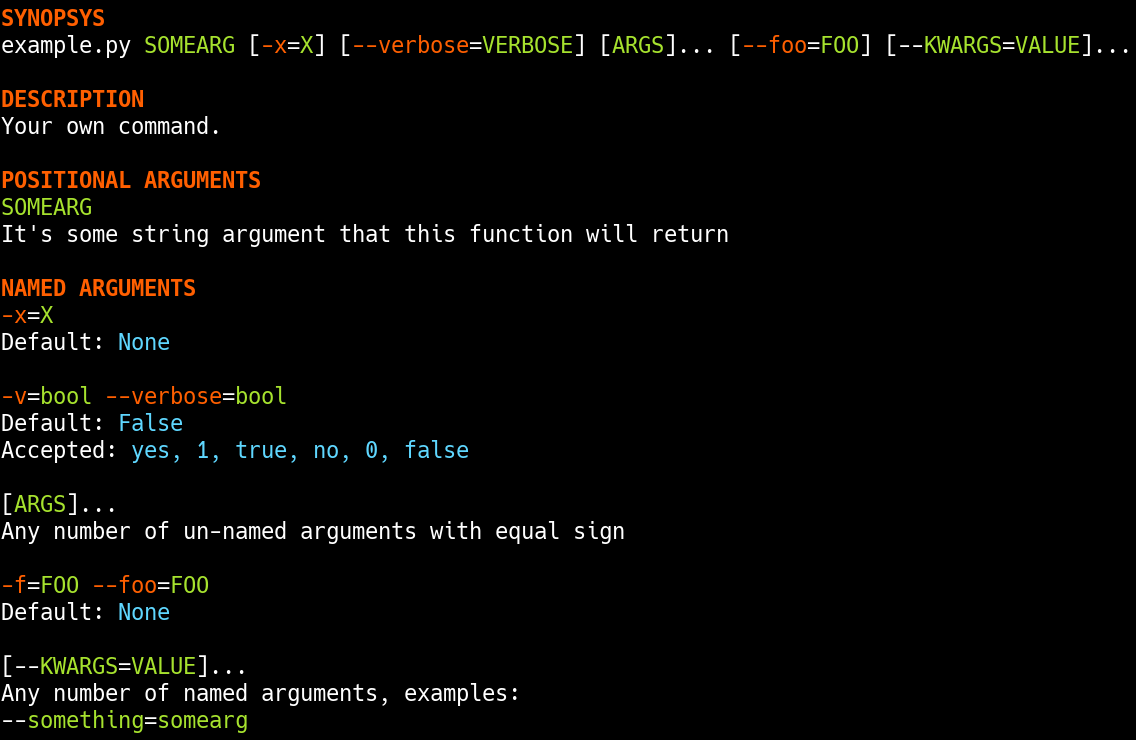

Posix style¶

You might prefer to have dashes in front of argument names in the typical style of command lines, you just need to enable the posix attribute:

cli2.Command(yourcmd, posix=True).entry_point()

In this case, help will look like this:

Testing¶

The parse() method will provision the

bound attribute which is a Python 3

BoundArguments instance, so you could test parsing as such:

cmd = cli2.Command(yourcmd)

cmd.parse('a', 'b', 'c=d')

assert cmd.bound.arguments == dict(somearg='a', x='b', kwargs={'c': 'd'})

Same if you want to use the posix style:

cmd = cli2.Command(yourcmd, posix=True)

cmd.parse('a', 'b', '--c=d')

assert cmd.bound.arguments == dict(somearg='a', x='b', kwargs={'c': 'd'})

Entry point¶

Another possibility is to add an entry point to your setup.py as such:

entry_points={

'console_scripts': [

'yourcmd = yourcmd:cli.entry_point',

],

},

Then, declare the command in a cli variable in yourcmd.py:

# if __name__ == '__main__': if block not required in entry point

cli = cli2.Command(yourcmd)

Group¶

Group can be used in place of

Command, and new commands can be added into it.

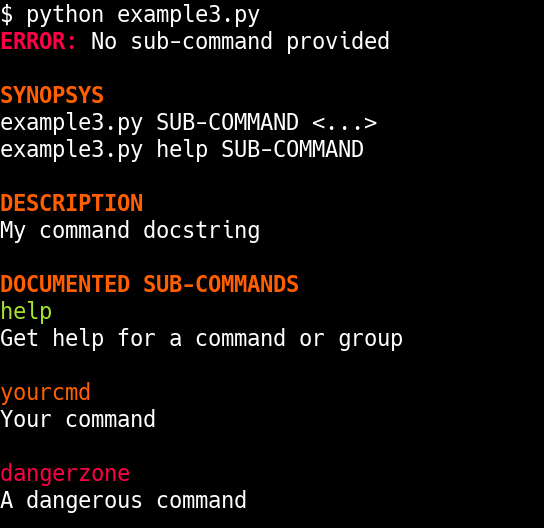

Decorator syntax¶

Example using cmd():

"""My command docstring"""

import cli2

cli = cli2.Group(doc=__doc__)

@cli.cmd

def yourcmd():

"""Your command"""

@cli.cmd(color='red')

def dangerzone(something):

"""A dangerous command"""

if __name__ == '__main__':

cli.entry_point()

As you can see, the decorator may be called with or without arguments, any

argument that are passed would override the default attributes from the

generated Command. Running this script without

argument will show:

Python API¶

Equivalent example using add():

import cli2

def yourcmd():

"""Your command"""

def dangerzone(something):

"""A dangerous command"""

if __name__ == '__main__':

cli = cli2.Group()

cli.add(yourcmd)

cli.add(dangerzone, color='red')

cli.entry_point()

Lazy loading: overriding Group¶

Equivalent example, but built during runtime, having the arguments at disposal:

import cli2

def yourcmd():

"""Your command"""

def dangerzone(something):

"""A dangerous command"""

class Cli(cli2.Group):

def __call__(self, *argv):

# you could use the *argv variable here

self.add(yourcmd)

self.add(dangerzone, color='red')

return super().__call__(*argv)

if __name__ == '__main__':

Cli().entry_point()

This is the same as the other command group examples above, but here the Group is built during runtime.

See the source code for the cli2 command, which implements an infitely lazy

loaded command tree based on introspection of the passed arguments with

extremely little code.

Lazy loading: using Group.load¶

You could also load commands more massively with the

load() method which will load any callable given as

Python object or as dotted python path, all the following work:

group = cli2.Group()

group.load(YourClass)

group.load(your_object)

group.load('your_module')

group.load('your_module.your_object')

Argument¶

Aliases¶

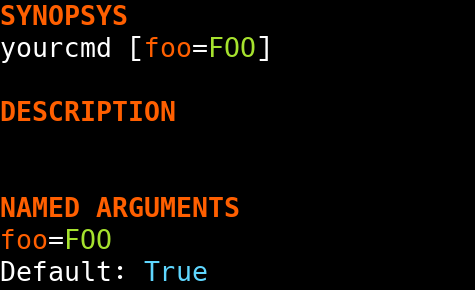

By default, named arguments are given aliases (CLI argument names) generated from their Python argument names. For example:

def yourcmd(foo=True):

print(foo)

cmd = cli2.Command(yourcmd)

cmd.help()

Will render help as such:

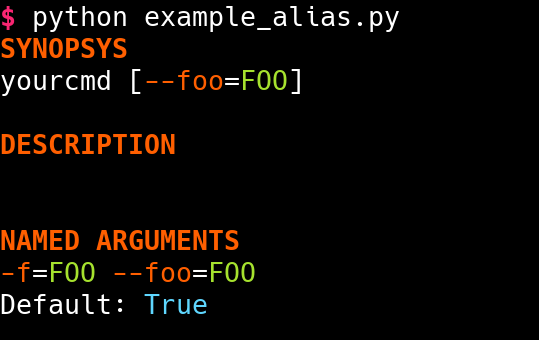

Posix¶

If posix mode is enabled, then a couple of dashes will prefix the Python argument name, and another one-letter-long alias with a single dash will be generated.

Overrides¶

You may overrides Argument attributes for a callable

argument with the arg() decorator:

@cli2.arg('foo', alias='bar')

def yourcmd(foo):

pass

This also takes a list of aliases:

@cli2.arg('foo', alias=['foo', 'f', 'foooo'])

def yourcmd(foo):

pass

This decorator basically sets yourcmd.cli2_foo to a dict with the alias

key.

Integers¶

Type hinting is well supported, the following example enforces conversion of an integer argument:

def yourcmd(i : int):

pass

cmd = cli2.Command(yourcmd)

cmd.parse('1')

assert cmd.bound.arguments == dict(i=1)

Boolean¶

Declare a boolean type hint for an argument as such:

def yourcmd(yourbool : bool):

You won’t have to specify the value of a boolean argument, but if you want to then:

- for

False: no, 0, false - for

True: yes, 1, true, anything else

Values don’t need to be specified, which means that you don’t have to type

yourbool=true, just yourbool or --yourbool in POSIX mode will set

it to True.

Since the mere presence of argument aliases suffice to bind a parameter to

True, an equivalent is also possible to bind it to False:

negate. It is by default generated by

prefixing no- to the argument name, as such, passing no-yourbool on the

command line will bind yourbool to False, or in posix mode by passing

--no-yourbool. Note that a single-dash two-letter negate is also generated

in posix mode, so -ny would also work to bind yourbool to False.

False¶

While the negates are set by default on boolean arguments, you may also set it on non-boolean arguments, just like you could override it like you would override aliases:

@cli2.arg('yourbool', negate='--no-bool')

def yourcmd(yourbool):

List and Dicts¶

Arguments annotated as list or dict will have CLI values automatically casted to Python using JSON.

def yourcmd(foo: list):

print(foo)

But be careful with spaces on your command line: one sysarg goes to one argument:

yourcmd ["a","b"] # works

yourcmd ["a", "b"] # does not because of the space

However, space is supported as long as in the same sysarg:

subprocess.check_call(['yourcmd', '["a", "b"]')

Typable lists and dicts¶

So, the above will work great when called by another program, but not really nice to type. So, another syntax for the purpose of typing is available and works as follow.

Arguments with the list type annotation are automatically parsed as JSON, if that fails it will try to split by commas which is easier to type than JSON for lists of strings:

yourcmd a,b # calls yourcmd(["a", "b"])

Keep in mind that JSON is tried first for list arguments, so a list of ints is also easy:

yourcmd [1,2] # calls yourcmd([1, 2])

A simple syntax is also supported for dicts by default:

yourcmd a:b,c:d # calls yourcmd({"a": "b", "c": "d"})

The disadvantage is that JSON decode exceptions are swallowed, but by design cli2 is supposed to make Python types more accessible on the CLI, rather than being a JSON validation tool. Generated JSON args should always work though.

Custom type casting¶

You may also hack how arguments are casted into python values at a per argument level, using decorator syntax or the lower level Python API.

For example, you can override the cast()

method for a given argument as such:

@cli2.args('ages', cast=lambda v: [int(i) for i in v.split(',')])

def yourcmd(ages):

return ages

cmd = Command(yourcmd)

cmd(['1,2']) == [1, 2] # same as CLI: yourcmd 1,2

You can also easily write an automated test:

cmd = cli2.Command(yourcmd)

cmd.parse('1,2')

assert cmd.bound.arguments == dict(ages=[1, 2])

Logging¶

By default, EntryPoint: will setup a default

logger streaming all python logs to stdout with info level.

Use the LOG environment variable to change it, ie:

LOG=debug yourcommand ...

LOG=error yourcommand ...

Or, disable this default feature with log=False:

cli = cli2.Group(log=False)

Tables¶

cli2 also offers a simple table rendering data that will do it’s best to word wrap cell data so that it fits in the terminal. Example:

cli2.Table(*rows).print()

Overridding default code¶

Argument overriding¶

Overriding an Argument class can be useful if you want to heavily customize an argument, here’s an example with the age argument again:

class AgesArgument(cli2.Argument):

def cast(self, value):

# logic to convert the ages argument from the command line to

# python goes in this method

return [int(i) for i in value.split(',')]

@cli2.arg('ages', cls=AgesArgument)

def yourcmd(ages):

return ages

assert yourcmd('1,2') == [1, 2]

Command class overriding¶

Overriding the Command class can be useful to override how the target callable will be invoked.

Example:

class YourThingCommand(cli2.Command):

def call(self, *args, **kwargs):

# do something

return self.target(*args, **kwargs)

@cli2.cmd(cls=YourThingCommand)

def yourthing():

pass

cmd = cli2.Command(yourthing) # will be a YourThingCommand

You may also override at the group level, basically instanciate your

Group: with the cmdclass argument:

cli = cli2.Group(cmdclass=YourThingCommand)

cli.add(your_function)

Global setup¶

A more useful example combining all the above, suppose you have two functions that take a “schema” argument that is a python object of a “Schema” class of your own.

class Schema(dict):

def __init__(self, filename, syntax):

""" parse file with given syntax ..."""

@cli.cmd

def build(schema):

""" build schema """

@cli.cmd

def manifest(schema):

""" show schema """

In this case, overriding the schema argument with custom casting won’t work because the schema argument is built with two arguments: filename in syntax!

Solution:

class YourCommand(cli2.Command):

def setargs(self):

super().setargs()

# hide the schema argument from CLI

del self['schema']

# create two arguments programatically

self['filename'] = cli2.Argument(

self,

inspect.Parameter(

'filename',

inspect.Parameter.POSITIONAL_ONLY,

),

doc='Filename to use',

)

self['syntax'] = cli2.Argument(

self,

inspect.Parameter(

'services',

inspect.Parameter.KEYWORD_ONLY,

),

doc='Syntax to use',

)

def call(self, *args, **kwargs):

schema = Schema(

self['filename'].value,

self['syntax'].value,

)

return self.target(schema, *args, **kwargs)

@cli.cmd

def build(schema):

""" build schema """

@cli.cmd

def manifest(schema):

""" show schema """

There you go, you can automate command setup like with the creation of a schema argument and manipulate arguments programatically!

Check cli2/test_inject.py for edge cases and more fun examples!

import inspect

import pytest

from unittest import mock

from .argument import Argument

from .command import Command

with open(__file__, 'r') as f:

lines = f.read().split('\n')

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

'kwargs, command, expected',

[

(

# test default enabled by default

dict(default=None),

[],

None,

),

(

# default should not be enabled

dict(),

[],

ValueError,

),

# test bools

(

# test default enabled by default

dict(default=True),

[],

True,

),

(

# note how defaults don't need annotation: they are enforced

dict(default=False),

[],

False,

),

(

# test enable

dict(default=False, annotation=bool),

['test'],

True,

),

(

# test disable, note how the annotation is needed

dict(default=True, annotation=bool),

['no-test'],

False,

),

],

)

def test_syntaxes(kwargs, command, expected):

kinds = [

inspect.Parameter.POSITIONAL_ONLY,

inspect.Parameter.POSITIONAL_OR_KEYWORD,

inspect.Parameter.KEYWORD_ONLY,

]

for kind in kinds:

kwargs['kind'] = kind

class TestCommand(Command):

def setargs(self):

super().setargs()

param = inspect.Parameter('test', **kwargs)

self[param.name] = Argument(self, param)

cbs = (

lambda: True,

lambda *a: True,

lambda *a, **k: True,

lambda **k: True,

lambda *a, test=False: True,

lambda *a, test=True: True,

)

for cb in cbs:

cmd = TestCommand(cb)

cmd.parse(*command)

code = lines[cb.__code__.co_firstlineno]

if isinstance(expected, type):

with pytest.raises(expected):

assert cmd['test'].value == expected, code

else:

assert cmd['test'].value == expected, code

def test_call():

sentinel = mock.sentinel.test_call

class TestCommand(Command):

def setargs(self):

super().setargs()

param = inspect.Parameter(

'test',

kind=inspect.Parameter.POSITIONAL_OR_KEYWORD,

default=sentinel,

)

self[param.name] = Argument(self, param)

# argument is passed when defined in signature

cmd = TestCommand(lambda test: test)

assert cmd() is sentinel

# but is not passed when not in signature

cmd = TestCommand(lambda: None)

assert cmd() is None

# we don't want no ValueError though

class TestCommand2(TestCommand):

def call(self, *args, **kwargs):

return self['test'].value

# argument value is available and passed as seen above

cmd = TestCommand2(lambda test: test)

assert cmd() is sentinel

# argument value is available and not passed as seen above

cmd = TestCommand2(lambda: None)

assert cmd() is sentinel

Edge cases¶

Simple and common use cases were favored over rarer use cases by design. Know the couple of gotchas and you’ll be fine.

Args containing = when **kwargs is present¶

Simple use cases are favored over rarer ones when a callable has varkwargs.

When a callable has **kwargs as such:

def foo(x, **kwargs):

pass

Then, arguments that look like kwargs will be attracted to the kwargs

argument, so if you want to call foo("a=b") then you need to call as such:

foo x=a=b

Because the following will call foo(a='b'), and fail because of missing

x, which is more often than not what you want on the command line:

foo a=b

Now, even more of an edgy case when *args, **kwargs are used:

def foo(*args, **kwargs):

return (args, kwargs)

Call foo("a", b="x") on the CLI as such:

foo a b=x

BUT, to call foo("a", "b=x") on the CLI you will need to use an

asterisk with a JSON list as such:

foo '*["a","b=x"]'

Admittedly, the second use case should be pretty rare compared to the first one, so that’s why the first one is favored.

For the sake of consistency, varkwarg can also be specified with a double asterisk and a JSON dict as such:

# call foo("a", b="x")

foo a **{"b":"x"}

Calling with a="b=x" in (a=None, b=None)¶

The main weakness is that it’s difficult to tell the difference between a keyword argument, and a keyword argument passed positionnaly which value starts with the name of another keyword argument. Example:

def foo(a=None, b=None):

return (a, b)

Call foo(b='x') on the CLI like this:

foo b=x

BUT, to call foo(a="b=x") on the CLI, you need to name the argument:

foo a=b=x

Admitadly, that’s a silly edge case. Protect yourself from it by always naming keyword arguments …

… Because the parser considers token that start with a keyword of a keyword argument prioritary to positional arguments once the positional arguments have all been bound.